OUR CULTURE (Return to T.I.)

The Japanese fishing village was started by

the adventurous fishermen who endured much hardship in a foreign country where

they were unable to speak or write English. Faced with such difficult

situations, they stuck together. The main factor for their success must have

been their mutual compassion.

This important feeling of compassion, I

believe, best describes the character of the Japanese fishing village on

Growing up on

Kindergarten – Bunch of clowns! From left, Kimio

Hatashita, Yoshio Hashimoto, Moto Asari, and Chikao Ryono

Some of my best days were in elementary

school, although there were some bad days, too. I believe most of us had the

roughest days in kindergarten with Miss Burbanks. She was tough! The carefree

preschool days suddenly came to a halt. We no longer could roam barefoot from

the

Mildred Obarr Walizer (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

Mrs. Mildred Obarr Walizer was principal

when I attended East San Pedro Elementary School. The name was changed to

Mildred 0.

Mrs. Walizer became ill when I was in sixth

grade, and Miss Morton, our manual arts (wood shop) teacher, selected Takashi

Yamamoto and me to build a breakfast tray. Takashi, our teacher, and I took the

tray to her apartment near

My teachers, as I remember: Kindergarten,

Miss Burbanks and Miss Chan; first grade, Miss Martin; second grade, Mrs.

Frigon; third grade, Mrs. Regan; fourth grade, Mrs. Brooks; fifth grade, Mrs.

Overstreet; sixth grade, Mrs. Robinson; seventh grade, Mrs. Dever; manual arts,

Miss Morton; agriculture, Mr. Logan.

Miss Garcia was our quiet, unsung teacher.

She acted as a trusted counselor and go between for the teachers and parents.

Communication was almost impossible because we had a peculiar situation: the

teachers couldn’t speak Japanese and the parents couldn’t speak English. From

kindergarten through seventh grade the student body was 99.9 percent Japanese

with two Caucasian students, a boy named Gus and a girl named Fern. (The two

Russian children attended later.)

The relationship between the teachers and

parents was warm, and they forgave each other’s shortcomings. There existed a

close kinship. Despite the difficulties in communication, the teachers had no

desire to transfer. This closeness was the envy of other school communities.

Miss Garcia also was instrumental in

starting the first parent teacher association. She was helped a great deal by

Mrs. Yokozeki. Miss Garcia also was responsible for starting a class for the

working mothers. I recall how Mom studied and practiced how to write her name.

The Fujin Kai (Ladies’ Club) was active with

much help from Mrs. Yokozeki, who understood and spoke English very well. She

and Toma-no-jiiyan also acted as the go betweens for the teachers and the

parents. Any item needed by the school was taken care of by Jiiyan. He

dedicated his life for the betterment of the

Landmarks behind our school were a Los

Angeles Fire Station, the U.S. Post Office, and the Fish and

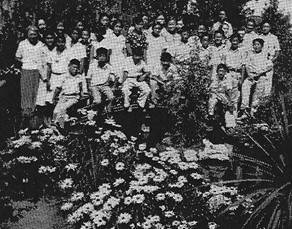

Our Group. Front row: Moritaka Nakashima, Hideyu

Uyeda, Koo Ito, Ryoji Terada, Iwao Hara. Rest, at random: June Nishida, Aiko

Nakamura, Kokane Nakanishi, Chizuru Nakaji, Iku Yamashita, Fumiko Hayashi,

Carrie Miyageshima, Hiroko Takahashi, Suzuko Joe, Michi Tanino, Sadako Yoshida,

Yukio Tatsumi, Yumiji Higashi, Masuji Nishino, Chikao Ryono, Kiyoshi Nakagawa.

Not a very good picture, but we can recall the names. Sorry I couldn’t identify

everybody. (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

Our Teachers – Dr. Davis’s Era. With Toma-no-jiiyan

and the teachers. I recognize Mrs. Frigon, Mrs. Brooks, Mrs. Regan, and Miss

Martin. Seated on the right is Miss Garcia. (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

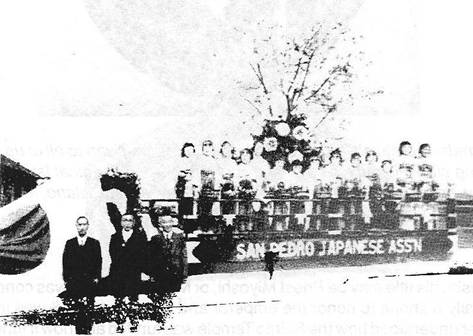

This project was made possible by Toma-no-jiiyan’s

unselfish effort. The float won a prize. (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

Mr. Tsurumatsu Toma, philanthropist. He was

Toma-no-jiiyan to all of us and “Jiiyan” to the teaching staff. He put his

heart and soul into making

Mr.

Miyoshi, his title may be Priest Miyoshi, or Miyoshi-sensei, was connected to

what was basically a shrine to honor the emperor and the ancestors. It was in

front of Judo Hall. I never understood how the

“Dai-Jingu” –

New

The

It was at this time (about 1936), the

We attended Japanese school after regular

school, from

The Japanese school teachers who tried so hard

to teach us to read and write the difficult language were Principal

lwamoto-Sensei, Kenkichi Murakami-Sensei, Shingu-Sensei, Furutani-Sensei,

Yamamoto-Sensei, and Tanaka-Sensei. When Iwamoto-Sensei retired, Ishikawa-Sensei

became the new principal.

Murakami-Sensei was a terrific story teller,

a talented teacher, and a professional photographer. Most of our family

pictures were taken by him, and he took the photograph of the Patriotic

cruising along the breakwater. I think he should have remained a photographer

instead of becoming a teacher.

Mom told me a story about Murakami-no-Jiiyan

and Bayan, Murakami-sensei’s parents. When I was small, we lived near the

Murakami’s. Bayan gave me goodies to eat so I would visit them. As I would go

around the dining room table, my head invariably hit the sharp corner of the

table. Within a short time, Jiiyan had rounded the corners of his favorite

table, which he had built.

For years, Murakami-no-Jiiyan was the first

visitor on New Year’s Day at our home. He always sang one song, a Japanese

ballad.

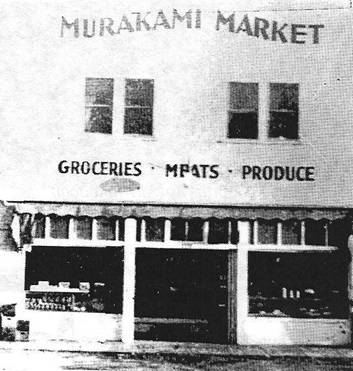

Mr. Motoyoshi Murakami, a very successful merchant

and our Baptist Church Sunday School teacher. Murakami-sensei tried hard to

teach us to play musical instruments. (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

There was a second Murakami—Sensei on the

lsland—Motoyoshi Murakami-Sensei. He owned the successful Murakami Market and

taught Sunday School. He was musical, and we enjoyed his trumpet solos at the

church service. He tried to teach us to play musical instruments, and I was in

his harmonica class. I was so proud of my Hohner Marine Band harmonica, but,

unfortunately, my musical talent didn’t match my desire, and my career came to

an abrupt end.

Our church groups and the island clubs

benefited from his generosity. I remember when the Judo Club toured

Sokei Gakuen and

Ikeda-Sensei and his family (Courtesy of Mr.

Takeuchi)

Sokei Gakuen’s Boy Scout Drum and Buble Corp 225

(Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

The

Isseis on the island had a difficult time

learning English because the society — social and business — was entirely

Japanese. On the other hand, the city-dwelling Japanese had contact with

Caucasians and learned English better. The same applied to American customs and

traditions.

Most of the families on the island ate

Japanese-style food. Steaks and roast beef or poultry was almost unheard of,

and much of the cooking was done over two or three burner gas stoves. Many

families were embarrassed at the relocation centers because they did not know

how to use knives and forks. However, during the Golden Era of fishing prior to

the war, many affluent families had slowly changed over to the Occidental style

of cooking and living.

Another part of life on the island was

transportation. In the early days only several business families had cars and

there were no buses. Without transportation, we couldn’t travel very far.

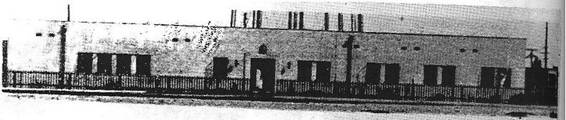

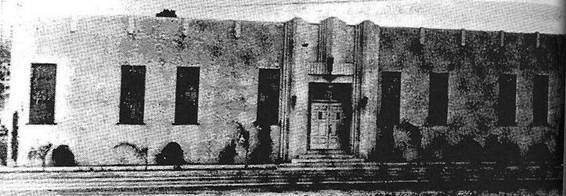

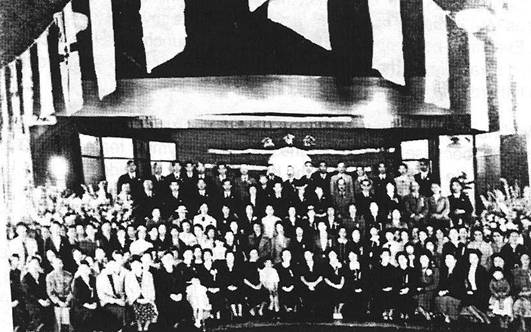

Our proud Fishermen Hall (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

The Fishermen’s Hall was the center of

activity on

During the silent moving picture era, we had

Japanese movies at the Fishermen’s Hall, usually once a month. The Japanese

movie company had a Benshi, a man who would narrate from the side of the

screen. He would also do all the talking parts of the actors and actresses. The

sound effects were created by paraphernalia such as drums and bugles. It was

always comical, if not disastrous, when the Benshi took the part of an actress,

especially in a love scene. The husky male voice never made it. The best Benshi

was Kawai Taiyo. Another narrator, whom we named Chon-mage, was the ultimate in

futility. He ruined all the tender, emotional scenes with his raspy voice. He

got his nickname because of his samurai hairdo. The most popular movie was the

Japanese “western,” a samurai sword-fighting picture called, chan-bara. The

guys went for a movie called “Tange Sazen,” about a one-eyed, one-armed

samurai. The girls would swoon with the popular, romantic movie “Aizen

Katsura,” starring Ken Uyehara.

There were many shops on

Mr. Kazuichi Hashimoto (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

Mr. Yosaburo Hama (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

Hashimoto and

Mr. and Mrs. Hirosaburo Yokozeki and son, David. He

was Executive Secretary Emeritus of the Japanese Fishermen’s Association.

(Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

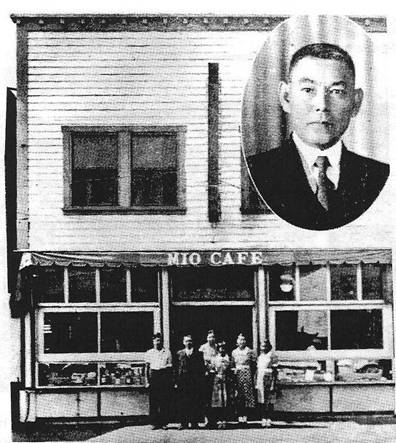

Mr. and Mrs. Zenmatsu Mio and family. (Courtesy of

Mr. Takeuchi)

The entire Mio group

Mr. Tetsunosuke Koiso, formerly the Tanishita

Grocery. Tom Tanishita’s father started this store. (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

Mr. Kinjiro Eto. Taro Eto (the son of Kinjiro),

bringing Asao Ishigaki and me home after a USC basketball game at the Pan

Pacific Auditorium on a foggy night, took us on a wild ride in his ’36 Ford

V-8. We were lost, but still got home at a decent hour. He should have been an

Indy 500 driver. (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

Mr. Koshiro Iriye.

Mr. Benkichi Maeda. Ben Sweet was our

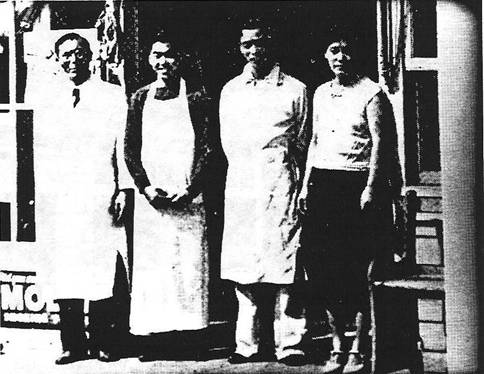

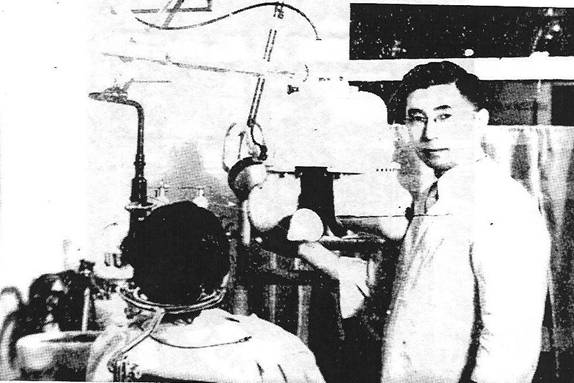

Mr. Itsuo Yamamoto. This was the meat market where

Nagao Henry “Duck” Iida was associated for a very long time. Note Dr. Kimura’s

sign above the meat market. This office was first occupied by Dr. Ito, who

commuted from

Mr. Daibe Ryono. The upstairs was occupied by Dr.

Fred Fujikawa’s office. This corner was first Mr. Hamashita’s grocery store,

and then used by the Ishino family. Remember Kanemasa? When Mr. Ryono took

over, he converted it into a stucco building and started his cafe. (Courtesy of

Mr. Takeuchi)

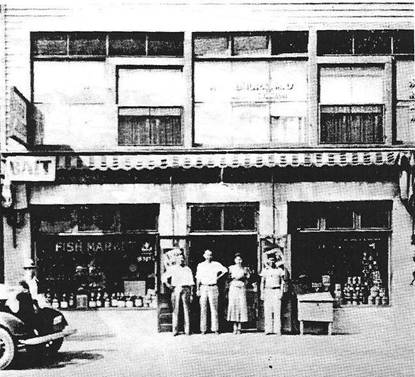

Mr. Shobei Takeuchi, Frank Takeuchi’s place. On this

section of

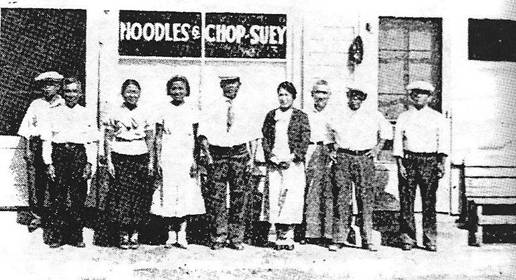

Mr. Nakamura. This was a popular noodle shop. Mrs.

Nakamura was called “Udon-ya no obasan” to everybody on the island. She always

smiled. She was a relative on my father’s side. Her daughter, Misuko often

visited our place when we lived at 641 Tuna St. She would play and look after

my sister, Misuko. I’d like to know where she is. Misuko was a good Japanese

dance performer. (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

Mr. Seichi Nonoshita (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

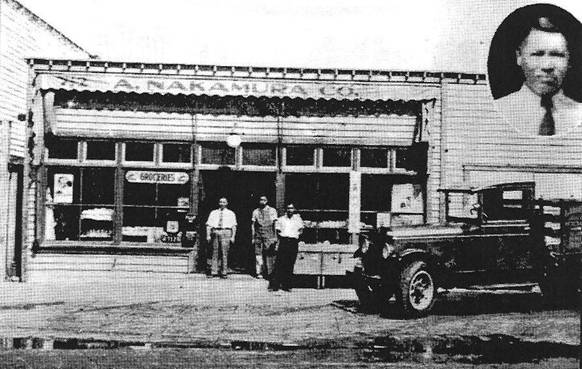

Mr. Akimatsu Nakamura; my classmate Aiko’s father’s

grocery store. I remember Mr. Omata, who was always so neat and well-dressed.

Mr. Omata traveled as far as

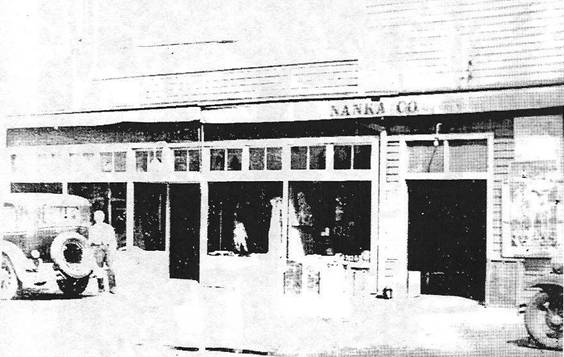

Nanka Shokai; Mr. Masakichi Tokunaga, Mr. Iwajiro

Asai – our one and only dry goods store, which was a favorite with the ladies.

(Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

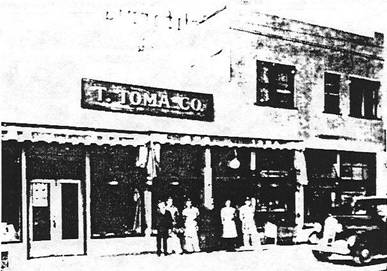

Mr. Sumiichi Toma; one of our more complete stores.

Next to the grocery store, Mr. Toma had a book and stationary department. Every

New Year’s, he would loan his Mochi-tsuki equipment to his customers. His

passenger car and trucks were constantly used by other Terminal Islanders for

civic affairs and outings. He was a kind man. The corner of his building was

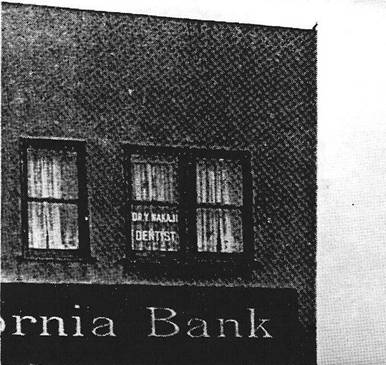

leased to California Bank and the second floor was occupied by Dr. Okami and

Dr. Nakaji. (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

Dr. Yoshio Nakaji’s office (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

Y.K. Sakimoto Store. Mr. and Mrs. Fukutaro Minami

with Toshiro Izumi and Yasushi Sakimoto. (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

Mr. Tomoji Wada and his Tofu-ya. Thanks to Mr. Wada,

all the

There were several other stores such as

Nakashima Grocery Store, Higashi Grocery Store, and Mr. Matsutsuyu’s Tailoring

and Dry Cleaning Shop. I do not have any other photographs, and my knowledge of

the other merchants is limited. I hope no feelings are hurt.

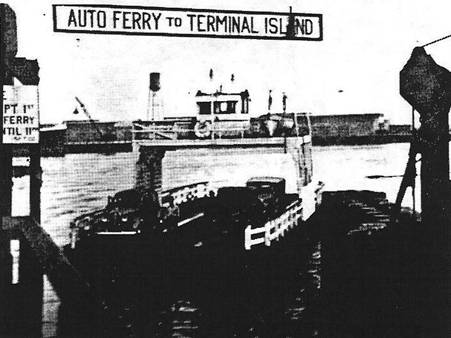

After elementary school came junior and

senior high school in San Pedro. Our experience was totally different than that

of other city school students. We had to walk to the ferry landing, take the

ferry across

(Do you remember Mary of the San Pedro Ferry

Landing restaurant who first introduced us to frozen Snickers and Milky Way

bars?)

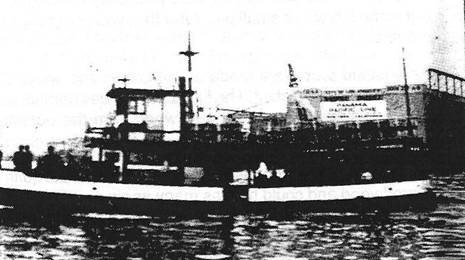

There were two ferryboats, Ace and Matt

Walsh, and the way the crew members would twirl the rope around the cleat as

the ferry boat came alongside the floating landing was a show in itself.

To be lost in a thick fog was the most

exciting adventure for us. Several times we almost broadsided a steamship. We

would hear the engine go full-throttle in reverse and out of the fog we would

see a huge gray wall, the side of a ship perhaps five feet away. At other times

we would miss the landing by turning too soon, and we would end up a quarter of

a mile south by the fish markets.

We adjusted well and did well at junior and

senior high school, taking part in sports and school activities, It wasn’t too

difficult to change from speaking Japanese in elementary school to all English

in secondary school.

Auto Ferry (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

Our Dependable Ferryboat (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

Corner of

I have often wondered who and how the Nihon

Buro (Japanese-styled bathtub) was designed in the early 1900’s to accommodate

all the Japanese in

The strict requirement of the Nihon Buro is

to scrub outside the bathtub; usually a bench is provided. After scrubbing, you

rinse your body thoroughly with hot water that you scoop out of the tub with a

small pail. After this, you are ready to step inside the tub and soak and relax

The

The tub for the communal bathhouse, made to

accommodate quite a few families, was made of thick redwood and could hold as

many as six people at one time These were called Kyodo-Buro

Each family had to maintain a continual

supply of firewood to heat the tub. One could judge the character of the

particular family by studying their woodpile A meticulous family had a neatly

stacked woodpile. Each piece of wood was cut to exact length and placed

alongside their house. Other families haphazardly stacked their wood and the

supply wasn’t plentiful. Keeping ample firewood was a big headache, a continual

source of stress and tension. There wasn’t a plentiful supply at the time, and

to make matters worse, most of us had to depend on the generosity of the stores

to borrow a truck

Although each family was responsible for its

firewood, with our

The families sharing the communal bathhouse

had to take turns cleaning and starting the large redwood bath tank. Each

family had to guarantee a nice hot bath for all the related families Kyodo-Buro

was fun for the guys because we would hit the tub about the same time to gab

about everything we could think of Maybe the girls needed more privacy

Next to the Nihon-Buro all the families had

a galvanized wire net tray. With the use of a light rope and pulley, the tray

could be hoisted up a pole to a point above the height that insects fly. It was

on this tray that families made a type of jerky. Usually the hi-mono was made

from sardine, mackerel, or Spanish mackerel which was split into a thin filet

and placed inside the tray. The meat, seasoned with salt, was toasted after

being dried in the tray. It was one of our favorite foods. My favorite was

anchovy or sardine hi-mono marinated with sugared shoyu and sprinkled with

sesame seed, toasted over an open flame. Another favorite winter food was a

nice fat sardine cooked in an open flame, especially the flame from the bath

firewood. This was a gourmet’s delight.

On Koi-Nobori — Boys’ Day—the family would fly

cloth fish on a pole, one koi for each boy in the family. Girls’ Day, along

with Bon-Odori, were big events. All the girls dressed in colorful kimonos and

danced in unison. Many pretty cho-chin (lanterns) decorated the dancing area.

An interesting and unique

Friendly Indian – Arrowhead. Leader George Fukuzaki.

Left: Assistant Leader Ben Fukuzaki. Back row: Chikao Ryono, Sueo Nakanishi, ?,

Kiyoshi Nakagawa. Front row: Toshiro Izumi, Takashi Yamamoto, Nobuo Iwasaki,

Ichi Hashimoto

At left, Wakayama-ken Picnic. At right, typical

sandlot ballgame. Masayoshi Masuda facing camera, Koo Ito holding the ball,

Chikao Ryono umpiring, Ryoji Terada pitching. Others present: Yasuo Tatsumi,

Yukio Tatsumi, Takashi Yamamoto. This was on the lot next to Takashi’s home on

Taiji-jin-kai Picnic

First Beach. Chikao Ryono, George Fukuzaki, Joe

Chartier, Ben Fukuzaki

The YMCA groups on

We played sandlot ballgames, and had the

usual gangs found in any little town in those days. We had the

I grew up with many friends, and we were

very close, probably because we lived so near to each other. The houses were

built by the canneries and the buildings were within 10 feet of each other.

We did not have any paved streets to speak

of because the blocks were divided by sandy alleys. Here and there, the

different canneries had built their own long block houses (Naga-ya) with one

communal bathhouse for every one or two rows of block houses. At times, four or

six houses would share one bathhouse.

The houses were constructed on raised

foundations with the bathroom built on one corner of the back porch. In the

early days, we had no heating system, no water heater and no refrigerator. The

ice-boxes were well made and the fancier ones were very efficient.

Our ice-men did not stand around socializing

— I imagine because the ice would melt. On the other hand, the grocery store

clerks who came to take orders would visit. The first ice-man was Mr. Hanazono

of San Pedro, my mother-in-law’s cousin. Mr. Shoji, Tiger’s uncle, was next.

The last ice-man was Mr. Yamanishi.

Our milkman was none other than the

prominent philanthropist Mr. Fred Wada, also known as Mr. Olympic. The crate

holding the milk was covered with cracked ice to keep it cold. Every time he

stopped to make a delivery, a bunch of us kids would jump on the truck and

scramble for the cracked ice. In those days ice was a big treat because we

couldn’t afford to buy ice cream. Besides, it was much more fun!

Mr. Wada later became the owner of several

produce markets. He was given the name “Mr. Olympic” because he boarded the

Japanese Olympic team in 1932 and helped again in 1984. He also established the

Keiro home for the elderly.

Japanese tradition and customs remained

strong in this almost completely Japanese village. Our parents were not

well-acquainted with the traditional American seasonal holidays. Christmas and

Thanksgiving were of secondary importance. There were no ovens to roast the

turkey because most families had only two or three gas burners. Besides, most

women would not have known how to roast a turkey with all the trimmings. As I

recall, pre-World War II stores did not stock turkeys and there were no

Christmas trees to be bought.

I don’t recall trimming the Christmas tree

as we do now. We started our Thanksgiving turkey dinner when I was in high

school. As we turned toward our so-called modern era, our lifestyle did change

to become similar to what we enjoy now. The daughters attending high school

were able to teach their mothers how to cook American dishes and roast meat.

The Obasan-tachi, on their own initiative, with more leisure time for themselves,

were now attending adult night school to learn to read and write English. They

also were learning how to color and dye fabrics, tailoring and flower

arrangement (Ike-bana). I still remember how proud my mother was the first time

she roasted pork and made apple sauce. She served the family with a complete

set of silver for a grand sit-down dinner. That same year she roasted her first

turkey for Thanksgiving dinner.

As I reminisce about the good days of

The ladies of

Terminal Islanders really enjoyed and

celebrated New Year’s Day, O-sho-ga-tsu. However, my father did adopt the good

old American custom of shooting off a shotgun on New Year’s Eve. My first

memory of the shotgun was when we lived behind the Franco-Italian Cannery. As I

watched Dad fire his shotgun, I thought how strong and manly he was.

The preparation for New Year’s Day always

started with mochi tsuki, the pounding of cooked rice — mochi-gome — with a

wooden mallet called a kine and a stone mortar called an usu. The rice was

cooked in a series of wooden trays, usually stacked one on top of another and

placed on a platform or base on top of a tub filled with water. The rice was

steamed with a good wood fire beneath the tub. The steaming had to start

several hours before the pounding.

The fellows would take over the mochi tsuki

when the steamed rice was placed into the stone mortar and the pounding began.

There would be three fellows with wooden mallets usually made out of a

eucalyptus tree. A fourth person would mix the rice as it turned into mochi.

The whole process would end with a one-on-one encounter between the mixer and

the pounder. The macho pounder would keep beat with the clapping and chanting

as everyone gathered to watch. The mixer would knead the mochi. The idea was

for the mixer to quickly pick up the hot mochi and make the pounder look silly,

hitting an empty mortar — kara-usu. It’s a shame our younger generation cannot

experience this mochi tsuki.

The women had their own party inside the

house. We could see them talking and whispering their secrets, and we could

hear their shrieks of laughter. Their job was to take the hot mochi and place

it on a large table covered with flour to prevent sticking. They shaped the

mochi into different sizes, some for traditional kasane-mochi topped with a

tangerine with leaves still attached. The big kasane-mochi always went to the

boat and was placed by the steering wheel inside the pilot’s cabin. Most of the

mochi were filled with bean paste to add taste.

Several families traditionally joined my

family so we often pounded more than 300 pounds of rice. The crew members and

some of my older brother’s friends would volunteer so we were never short of

manpower. Yutaka Yoshimoto, a close family friend, always came to help. Similar

mochi-tsuki would be taking place throughout

After mochi-tsuki, the biggest chore was the

women’s as they prepared for the New Year’s feast. The Japanese food invariably

involved the cleaning and chopping of the food. In those day, we did not have

the modern kitchen gadgets, so everything was done by knife. The hardest part

was the sen-giri (one thousand slice, meaning very thin slices). Then came the

making of sushi and teriyaki chicken and pork. Cooking the traditional black

beans took the longest time, but the beans were a must because they meant long

life. Naturally there were various seafoods, but mainly tuna sashimi.

The center decorative tray included a large

lobster or Tai fish and was the main piece for the dining table. The food on

the tray had its own special meaning and was placed in odd numbers. Naturally,

the omiki had to be plentiful and hot.

New Year’s Eve meant consuming Toshi-koshi

soba, a Chinese style dark noodle, at

In the morning we started the New Year with

the delicious o-zo-nin. The entire day is still celebrated with relatives and

friends dropping in for the New Year’s greeting. In the olden days, Isseis were

much more versatile and genki than the people today. They worked hard but knew

how to relax and celebrate. The lsseis visiting us to pay their respects would

always sing and dance— individually or in a group— when other friends showed up

at the same time. Most made up in spirit what they lacked in singing or dancing

talent.

Our family still gets together on New Year’s

Day with relatives and friends easily numbering more than 40, but we have no

hand-clapping and singing. Absolutely not! Sad.

The Isseis were a great generation who knew

how to live.

This very unusual fishing village was one

big, happy family. Everyone knew each other. The doors were never locked and

you could stop at any house and ask for a glass of water. All you had to do was

say “Oba-san.” This changed as the canneries became busier and started to

expand which brought in a completely different and strange work force. Soon we

began to hear how different families were robbed, and we started to lock our

homes: Still there was no police force on the island. Several years prior to

the evacuation, the Harbor Department started to deploy a few patrols.

Strangely, they were never seen after dark; the patrols seemed to work bankers’

hours.

There were three major fires in

The Long Beach Earthquake of 1933 was a

major event which we all remember with the thought, “What would have happened

if it had occurred about an hour or so later.” The quake happened about

Another event to be noted was the labor

conflict between the AFL and 010 in 1939. The conflict became partially racial

in nature because the Italians and the Japanese favored the AFL and the

Slavonians were adamantly for the ClO. There was a threat of burning the houses

on the island. The Los Angeles Police Department assigned detectives to every

corner of every block, and the students had to take an assigned route to Dana

Junior High and

In this small Japanese fishing village, the

early Isseis were very ambitious and far sighted. In 1918 the first newspaper —

The San Pedro Weekly Journal — was started by Mr. Hatsutaro Sarae. Two men from

Taiji, Etsujiro Yonemura and Nobuji Yura, took over the paper and renamed it The

HarborJournal. In 1928, Jiusho Hiraga took over the business and became

publisher. He renamed the paper the Southern California Coastal Journal.

We were fortunate to have five capable

dentists, Dr. N. Ohira, Dr. Yoshimura, Dr. Yoshio Nakaji, Dr. Fujii, and Dr.

Yoshi Nakamura.

The

first barber to cut my hair was Mr. Ozawa. And what a disastrous affair! I remember

running home, crying, and trying to hide my half-finished scalp. I never went

back to him. Later our other barbers were Mr. Hanamura (

The Crew (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

Mr. and Mrs. Kosuke Takeuchi. It was Mr. Takeuchi who

researched and wrote the book, “History of San Pedro.” He recorded all the

historically pertinent data in his book and left it for us to study. Thank you

very much, Mr. Takeuchi. (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

Dr. Shigeichi Okami (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

Dr. Fred Fujikawa. I am sorry that Dr. Ito and Dr.

Kimura’s pictures were not available. I faintly recall another M.D. who took

over after Dr. Ito. (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

Dr. Y. Yoshimura (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

Mrs. Ishii (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi) Misako Ishii

(Mrs. Kiyoshi Shigekawa) was our always helpful and reliable pharmacist. Frank

Takeuchi was our other pharmacist.

Dr. and Mrs. Fujii (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

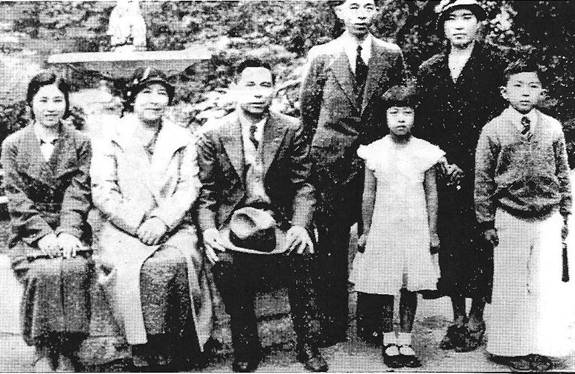

C. Ryono family on their trip to

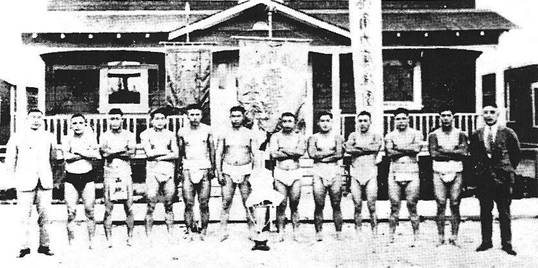

Championship Sumo Team (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

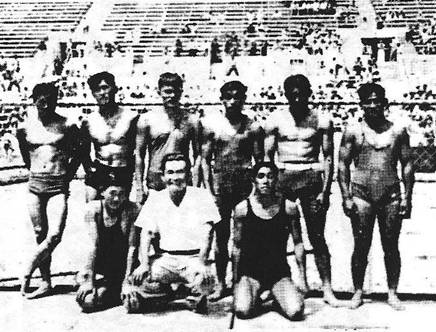

Skipper Swimming Team (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

Judo (L-R) Tamikazu Hamazaki, Kiyoshi Sakimoto, Mr.

Yokoyama, Iwao Shirokawa, Tom Tanishita, John Ryono, Teacher: Yajyu Yamada

Kendo – Teacher, Dr. Fuji (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

San Pedro Skippers

Early 1900 prominent personalities. Back row: four

unidentified persons and Mr. Tetsunosuke Koiso, third from left, and Mr.

Yosaburo Hama, fifth from left. Middle row: Mr. Kazuichi Hashimoto, Mr. Momota

Okura, Mr. Kobei Tatsumi. Front row: Mr. Jiusho Hiraga, Mr. Yasutaro Tanaka.

(Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

Seinen-kai. Back row: Kiyoshi Sakimoto, Tamikazu

Hamasaki, Iwao Shirokawa, Yasushi Sakimoto, Yutaka Yoshimoto. Front row: John

Michio Ryono, Tadao Ikari, Isamu Fujita. (Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

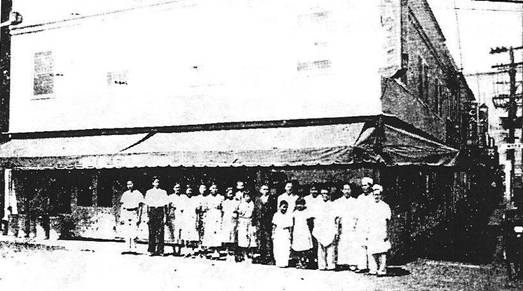

Mutual Fish Co. Katsuo Hayashi and Katsumi Yoshizumi

worked here for a long time. (Courtesy

of Mr. Takeuchi)

The golden years for the Terminal Islanders

was in full swing from 1934 to

Even if

The reaction of our government to

However, evacuation and relocation gave us

an impetus to assimilate with a wider society. Our circle of friends became

larger and our horizon became unlimited. After all we did have much to learn.

Evacuation had its positive effects, but what a price we had to pay.

With

The women hard at work. (San Pedro News Pilot)