FISHING INDUSTRY (Return to T.I.)

The history of

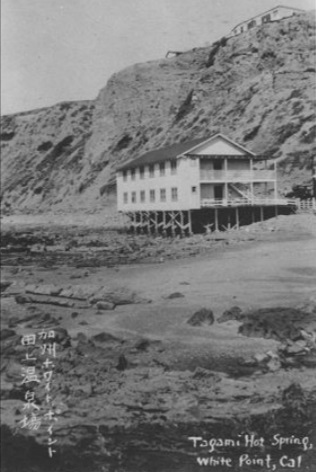

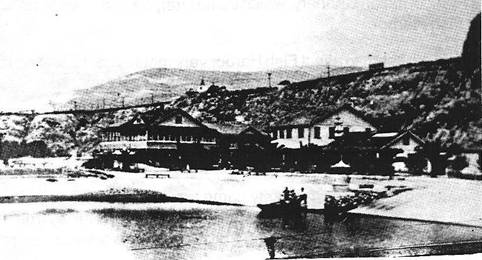

White Point Hotel, location of Issei Cove. (Courtesy

of San Pedro News Pilot)

White's Hot Springs |

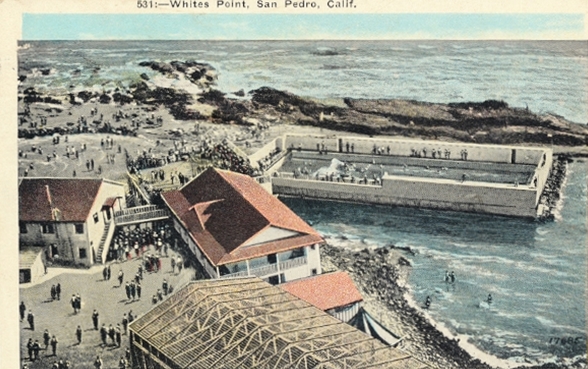

Whites Point Hot Springs |

Saltwater Pool - 1922 |

In the beginning, dressed only in flimsy

loincloth and armed with long knives, the Japanese dove for abalone. In those

days abalone must have been plentiful and located not too deep underwater. The

water of

The abalone were boiled, cooled and put on a

wooden rack to dry. The process was a disaster at the beginning, according to a

story by an Issei (first generation person). When the meat was cooked in a

shell and left out in the sun to dry, germs would enter through the breathing

holes of the abalone shell and spoil the meat. The solution was to shuck the

meat and dry it.

(Abalone meat, especially from the young and

tender ones, was delicious. As a youngster I would have a piece of dried

abalone in my pocket and every so often I would take it out, and slice a thin

piece with a pocket knife. I’m sure you did the same. Who can forget the delicious

taste of golden brown, dried abalone?)

By November 1901, the hardy fishermen were

rowing their tiny boats 25 miles to

The fishermen were canning abalone from

November to May for the Asia Co. in

The prosperous abalone industry came to an

abrupt end. The ugly horn of racial prejudice stuck out in 1905 when

Soon after the abalone industry stopped,

about the end of 1906, Mr. Zenkichi Hamashita purchased the 24-foot boat,

(Mr. Hamashita earned $3 to $4 a day for his

fish catch, and the farmers were only earning $1.50 a day. Thirty years later,

in 1937, I worked in a supermarket produce department from

A group of Japanese joined Mr. Hamashita in

San Pedro in the spring of 1907. They were Hikotaro Sarae, Nakasuji, Hayashi,

and Tsuchiyama Asari (this name puzzles me because it has two surnames). These

names are familiar on

These pioneering fishermen used small boats,

powered with 5 to 10 hp gasoline engines. In

Usually a single fisherman would operate the

boat, jigging a long line with jigs, or using line with baited hooks attached

to a floating pole.

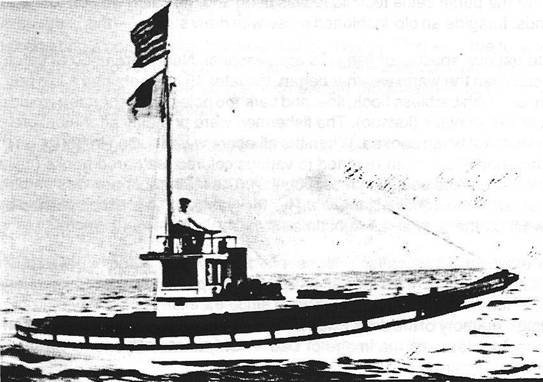

From my little knowledge of fishing boat

history, I believe these jig boats were called lampara in

Jig boat or lampara – Mr. Yoshimatsu Hamaguchi.

(Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

In 1910, the San Pedro Fish Co. was founded

by Yoshitaro Tani, Dentaro Tani, Torao Takahashi, Hikotaro Sarae, and

Kaneshima, who were mentioned in the Genesis section of this book. These early,

hard working fishermen sold their catches to the

The fishing boats were becoming larger and

the gasoline engines were 7, 10, 12, and 20 horsepower. Sardines were also in

their catches, and bait tanks were starting to be used to hold live anchovies.

This started the local tuna fishing industry.

The 45 hp boat eventually became popular

because the fish were plentiful, especially the sardine. The price of albacore

was $30 to $35 a ton, which necessitated a larger boat with a bigger pay load.

To understand the boats and fishermen, it is

important to know a bit about the fish. The method used to catch the fish

depended on the type of fish that was wanted. In addition to jigging, there was

the braile net. It was used solely for mackerel, which is more or less a

surface fish feeding on plankton and anchovies. They tend to school, so a

braile net was the method of choice. Albacore hardly ever school and are found

at various depths. The long-line, or jigging, was the way to catch them. At

times, live anchovy bait, using hook, line, and pole would be used. As for rock

cod, they are in deep water as far down as 75 fathoms (one fathom is

approximately 6 feet). The method of fishing was with long line (hand or pole),

baited hook, and very heavy lead sinker. Blue fin tuna will school, so later

the purse seine technique was used and the catch was on tonnage scale, not

pounds. Imagine an old-fashioned purse with draw strings ─ this is the

basic principle.

The various species of fish are also

seasonal. Nets were used to catch sardine in winter. When the warm weather

began, the later 45 hp boats had a live bait tank in the stern, and with

barbless hook, line, and bamboo poles, the fishermen would go after the tuna or

the skipjack (katsuo). The fishermen were primarily after albacore because of

its white meat when cooked. When the albacore were feeding in frenzy on the

surface, the Japanese fishermen resorted to various colored feathered hooks

(called kozu-no with red and white being the most popular). The feathered hook

was barbless, making the fish easier to unhook in mid air. This tricky release

was accomplished by snapping the wrist on the pole at the right time.

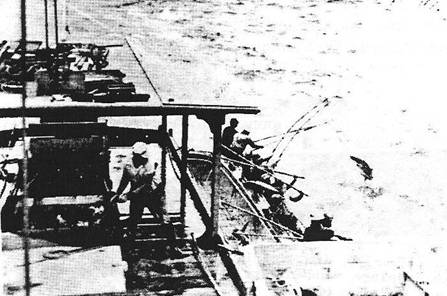

This picture from Mr. Takeuchi’s book shows the 45 hp

(Shiju-go-bariki) fishing boats on the left side and the jig boats on the right

side. The 45 hp boats were naturally longer with wider beams and the sterns

tapered a little. The Lamparas were smaller and the stern tapered almost to a

point.

(In a recent conversation with several

fellows from

Besides chumming with anchovies to keep the

fish near the boat, I watched Dad and the crew take a bamboo pole with a little

cup, or just a fine point, and beat the surface of the water creating a noise similar

to a bunch of anchovies. That kept the tuna active and near the stern portion

of the boat. The fishermen were adept and quick to employ techniques learned in

their native village, with certain modifications to catch fish in

It is no wonder that in 1917, the Pacific

Fisherman Journal wrote:

“The Japanese taught the Americans and all

others how to catch fish in commercial quantities, and they are the best

fishermen in the game. As a result, the packers vie with each other in

providing them with attractive quarters close to their respective plants.”

This article is so true. As I was growing

up, it was easy to observe how the successful boat owners carried more clout

with their canneries than less successful owners. The plants would extend

themselves to keep the captains happy; they didn’t want to lose their

contracts. I remember going with Dad to Van Camp’s office. He would approach

Mr. Gillis, the general manager, and in his broken English ask for this and

that. Invariably, he was successful.

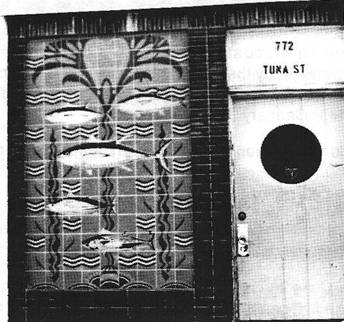

Formerly the entrance to the Van Camp office.

Presently office of the Pan Pacific Cannery, about

1980.

The canneries rented small houses to the

fishermen. I know my dad rented many houses under his name. Besides the usual

number for his crew members, he had homes for his friends and the unlucky

people. At times, he paid rents for others. The rent was about $6 a month. The

quarters were not naturally attractive. The people made them that way by

planting flowers and building fancy fences.

Mr. Takeuchi’s book lists numerous fishing

boats at this early period. There were many lamparas and 45 hp boats, and some

boats a little larger than the 45 hp. Purse seiners and tuna clippers came much

later.

How boats were named is interesting. My

father started with a little boat between lampara and a 45 hp in size, and he

named it Chitose, after a Japanese battleship on which his younger brother was

serving. Others named their boats using their hometown name. The Fujii family’s

boat was Kushimoto, the name of their village. Later on, when they bought a larger

boat, it was Kushimoto No. II. The same was true with the Hashimoto family and

Ubuyu Maru.

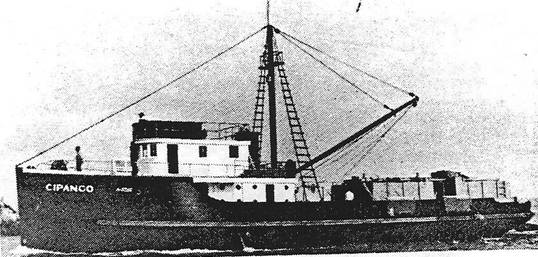

Ubuyu Maru ─the owner was Mr. Ryokichi

Hashimoto. Mr. Hashimoto was a quiet man. I remember that he would often travel

with Dad when they fished at

I loved the name Naruto, a boat owned by Mr.

Saka of Taiji. Naruto sounded royal and supreme to me. Another name I liked was

By the 1930s, the number of smaller boats dwindled.

Some successful families returned to

The fishing canneries were a vital part of

the fishing industry and life on

According to several books, the first

cannery on

Cal Fish became the Southern California Fish

Cannery. Mr. Wood eventually left, but years later, when the cannery had

financial difficulties, he was its president. When he retired after about 26

years, Larry Holland became the new owner.

(An item to remember, Mr. Wood and Mr.

Holland were very supportive of the Japanese families during the trying time of

evacuation.)

In 1903, Mr. HaIfhill of the Southern

California Fish Co. established the logo “Chicken of the Sea” with the help of

Mr. Wood.

Japanese fishermen started the San Pedro

Fish Co. in 1910, and at about the same time, Chinese businessmen started a

cannery which later became Franco-Italian Fish

In 1912, according to the San Pedro Historical

Society’s book and remembering what Dad had told me, Mr. Wood started his own

company, the California Tunny Co. with Paul Eachus. It was bought by the Van

Camp family when they came to San Pedro in 1914. A disastrous fire hit the Van

Camp Fish Cannery in 1915, and it consequently was bought out by White Star

Cannery.

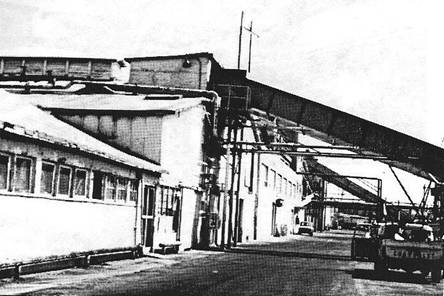

Looking down

(Some of you must remember Gilbert Van Camp

Jr., who played tennis for

According to Mr. Takeuchi’s book, the

following canneries were operating as of 1915 to 1916: Van Camp Fish Cannery,

White Star Fish, Ambrose (?), North American, Coast Fishing,

That same year, Martin Bogdanovich’s French

Sardine Co. — later the prominent Star Kist — started, along with Joe

Mardesich’s Franco-Italian Cannery (

Part of Van Camp’s International branch.

When World War I started, there were more

canneries operating in the harbor. The Van Camp Cannery recovered and absorbed

three other companies: International Packing Co., which the Japanese called

In-ta, a way of saying International, and where Mr. Nakasuji was foreman;

Neilson and Kittle, which the Japanese called Ne-ru-son; and White Star, where

Mr. Fujikawa was foreman.

Front of In-ta (formely International) cannery, about

1980.

In 1935, the

The primary station where the fish are vacuumed

through the large hose

from the hold of the boat to the cannery, about 1980.

Overhead structure. The fish are cooked and canned

below.

(For the breakwater project, Mr. Kinoshita

had to sacrifice his boatyard and machine shop. I remember Mr. K. Shiroyama

having his boat,

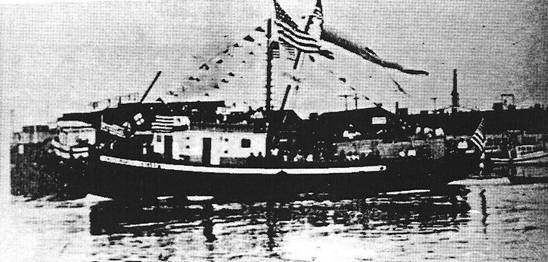

The city of

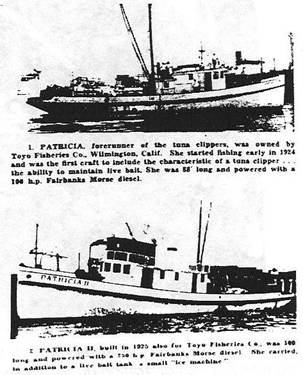

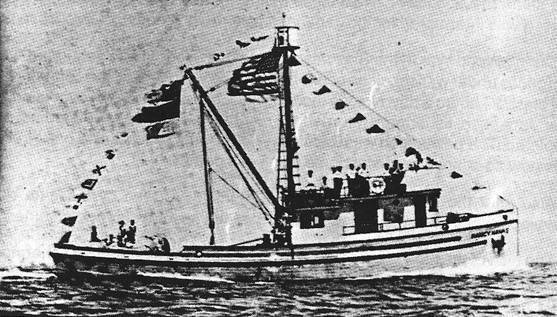

Patricia and Patricia II. Pacific Fishing Journal

The Japanese fishermen were the first to

think about live bait tanks and “ice machines” to preserve their tuna catches.

The “ice machine” was, in essence, the use of salt water to keep the fish cool.

Patricia Il can be called the first tuna clipper because it concentrated on

tuna catches only. I believe they were already fishing the

After World War I, boats became larger, the

nets longer and deeper, and the bait tanks much bigger. As the nearby fish

sources became scarce, the fishing ground moved further away, extending far

south below

The age of the popular purse seiners, 65

feet to 100 feet or longer, was ushered in about this time.

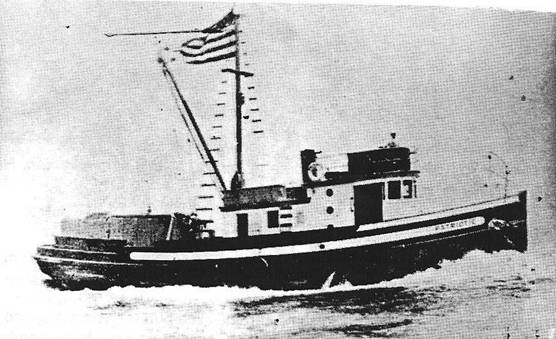

Patriotic – Chiyomatsu Ryono. Built at Harbor Boat

Shop in 1928.

I remember when the Patriotic was built by

John Rados and his Harbor Boat Shop. He had already launched

San Lucas – Dentaro Tani. One of the premier tuna

clippers prior to World War II. Mr. Tani, who previously owned

The purse seiners were versatile, catching

sardine in the winter and local blue fin in the summer. When both of those were

more or less fished out, the boats were used for mackerel. However, before

purse seiners could truly establish themselves, the awful Depression fell upon

us.

The Depression left a lasting memory for me.

The folks would buy socks that were much too big for me. The reason behind this

madness, I later found out, was that each time there was a hole in the toes,

Mom would snip off that section and sew the ends together.

We suffered because Dad invested everything

in building Patriotic in 1928. Times were difficult for everyone. At about this

time a loaf of bread was 5 cents and the family was fortunate to have meat

(weiners) once a month. Grocery stores must have had it rough because they

probably carried credit for all the starving families.

It was during the Depression that I had my

own experience in a cannery. I was 13 and to help out I went to work along side

the ladies. Dad said if Dr. Okami and Rev. Yamamoto worked at the cannery as

youths, my older brother and I could do the same. He invested in two buckets,

two knives, two oil-cloth aprons, and two pairs of boots and sent us off to

Linde Fish Cannery. We worked side-by-side with the ladies in their white

uniforms and white hats, chopping the heads off sardines. We worked hard. I

wasn’t about to be outdone by the “Obasan” bunch. I couldn’t take the hazing.

They were constantly laughing and saying, “Look at Chika-chan. He’s working so

hard not to be outdone.” It was almost sexual harassment! The work came to a

glorious end just two days later when Brother and I went on strike. Dad never

did recover his financial investment!

Dad was fortunate to have a friend, Mr.

Charles Houghton, a marine insurance broker who was brought up in

The

following are pictures of some of the purse seiners owned by the Japanese

fishing families. Many of the other boats are omitted only because I was unable

to obtain their pictures. I apologize to those families. Most of the pictures

below are taken from Mr. Takeuchi’s book. The boats not shown are: Silver Gate,

Richness, Congress, Cleopatra, Costa Rica, Francis, Liberty Girl, Success,

Onion, Silver Ware, Advance, Stanford, Senorita, Yukon, Eight Brothers, Amazon,

Emblem, Ohio II, Example, Star, New World.

Boats tied up at the

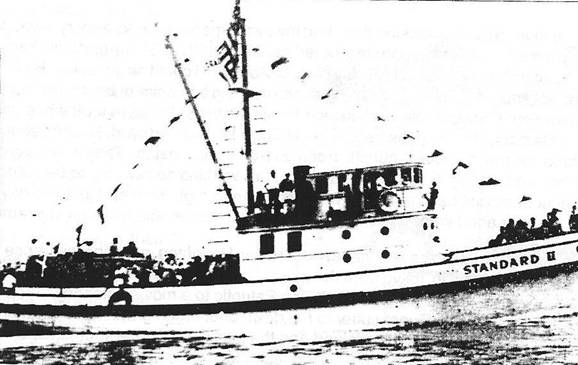

One of the more popular purse seiners, the Stanford

II. The owner, Mr. Jinshiro Tani (Tani-no-oyaji) was one heck of a man.

(Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

The Sweet II was owned by Mr. Sanzo Oka, a classy

gentleman. I always thought of him as a man in a charcoal gray and white

striped suit with a matching necktie. He was a tall, slender man. (Courtesy of

Mr. Takeuchi)

Westmaco – Mr. Matsukichi Miyagishima. (Courtesy of

Mr. Takeuchi)

White Rose – Mr. Shigematsu Ishikawa. (Courtesy of

Mr. Takeuchi)

Nancy Hank – Mr. Yohei Suzuki of Shizuoka-ken.

Perennial top boat in

Linde – Mr. Kinsaku Yamasaki. Another tough man from

Shizuoka-ken. He liked his cigars –

The industry recovered from the World

Depression. The economic boom was soon in full gear and it was full steam

ahead.

The fish were plentiful, especially the

sardine. The purse seiners were coming back from short trips loaded with them.

The average load must have been nearly 100 tons. The Italians and Slavonians

were outfishing the Japanese in number and tonnage.

The Patriotic loaded with mackerel, about 1957.

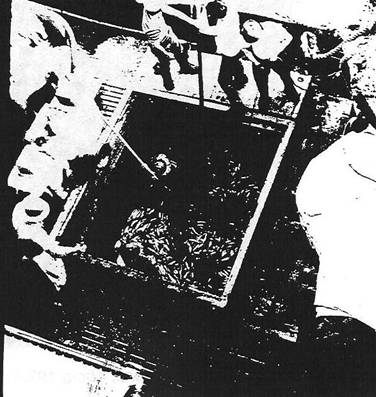

The Patriotic unloading mackerel through a giant

vacuum hose in about 1957. This method was put into operation during the

post-World War II era and tried at Southern California Fish Cannery. The first

boat to try this successful innovation was the Patriotic, shown with a full

load of mackerel.

Unloading, about 1957.

Unfortunately, the prosperity was not to

last long. Tonnage limits were instituted, but it was too late. The sardines

were gone from the nearby sea because of overfishing. The next fishing ground

was

During World War II, the Slavonian, Italian,

and Portuguese fishermen did well. With top prices under war condition economy

and with fish plentiful, the canneries were going full blast, 24 hours a day.

No one thought of the consequences of overfishing. When the few Japanese

fishermen returned to resume their trade, the sardine were totally depleted. The

prize catch was Pacific mackerel. This species also has been overkilled. It is

now so scarce that local purse seining is dead.

Also after the Depression, year-round

hunting for tuna by the tuna clippers was developing, but it was at a slower

pace than the spectacular purse seiner.

The bulk of the tuna clipper fleet was made

up of the Portuguese fishermen from

The tuna clippers caught their tuna with

hook, line, and pole. For the larger tuna, 100 pounds or more, there would be

two to three men on one hook.

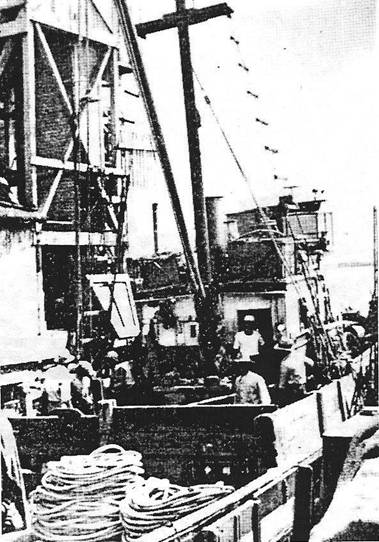

Note two poles on one line and how the fishermen are

working from an iron platform, just about submerged on the surface of the

water. The lone man on top is throwing anchovies to keep the tuna feeding.

“Chumming” attracts the fish and keeps their attention. (Courtesy of Mr.

Takeuchi)

Fishermen on single poles. The fish are smaller.

(Courtesy of Mr. Takeuchi)

My father was a pioneer in studying the

possibility of using a spotter airplane to find schools of fish. When we lived

at

(I remember playing with his oldest son,

Tetsuo, when we were kids. He gave me an Erector set for Christmas one year.

After 65 years or so, I still have it stored in the attic. I cannot get my

grandchildren interested in it. As you know, kids today are so sophisticated.

They are totally into computers.)

The

post-war picture of tuna clippers also changed. Tuna became harder to catch and

more expensive as boats had to venture further south after overfishing the

Mexican water. New concepts and techniques were desperately needed if the tuna

industry was to be saved.

Two

factors helped preserve the industry. The first was the introduction of the

power block, which revolutionized the way the crew pulled in the net. The power

block was introduced by the purse seiner, Anthony M, with terrific success.

The

second factor was the foresight and imagination of a Terminal Islander,

“Yankee” Kosoroft (I hope the spelling is correct). Yankee bought a naval

minesweeper, named it the “Yankee Mariner,” and converted it to a large purse

seiner, a novel idea. This boat used a large net — as long as three-quarters of

a mile — handled by the power block. It also was very deep. It was nothing forthe

“Yankee Marl ner” to catch 50,75 or 100 tons of tuna atatime, compared to the

clippersthat could only catch about 20 tons. This made bait and pole fishing

from tuna clippers obsolete.

The

Yankee Mariner’s trial run to

(We

all remember Yankee’s younger brother, Jimmy. The Kosoroffs were the sole

Russian family on

The

success of the Yankee Mariner led to the conversion of all tuna clippers to

super purse seiners. The race was on, larger boats to accommodate larger

catches and larger nets, bigger engines for more speed to get to distant waters

faster. They were already using brine tanks and more efficient refrigeration systems

to hold large catches. Modern super seiners are even air-conditioned and have

showers with hot and cold running water. They have the latest electronic

equipment, computers and self-steering systems.

By

1980, all the big seiners were engaged in large scale tuna operations in

foreign P countries such as

What

next? I do not know. I fear the future appears bleak. Modern electronic

equipment plus bigger boats and bigger nets are too much for the fish to

compete against. Where will be the next fishing ground? Already our

Maguro-sashimi is coming from the distant waters of

(

A strong, international conservation law is

needed to insure a permanent population of marine life. Ecological balance is

imperative. We cannot overkill.