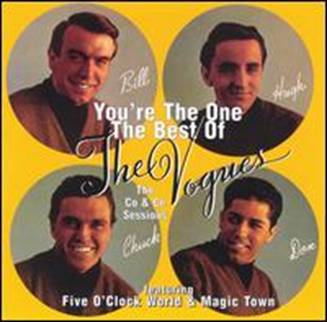

THE VOGUES: THEY'RE THE ONE

By Chuck Miller

It's the fall of 1965. For three of the most popular music

groups of the 1960's, their creative output was unmatched. The Rolling Stones

had just reached #1 with their song "Get Off My Cloud." The Supremes'

"I Hear A Symphony" would reach #1 that

season, as did the Beatles' "Yesterday."

But among those phenomenal recordings was another disc - a

debut 45 by four men from

This was the start of the Vogues, a quartet whose tight

vocal harmonies were reminiscent of street-corner doo-wop; a group whose music

later evolved into million-selling easy listening traditional pop. Between 1965

and 1969, the Vogues had 14 hits, four of which hit the Top 10.

But the Vogues were more than just a hitmaking

group. They were also four men with family values, who cared as much about

their wives and children as they did their performing careers. In the end, it

was the choice between family and career that brought an end to the Vogues. But

their music lives on - from "music of your life" radio stations to

sound clips on popular TV shows.

The nucleus of the Vogues began in 1958 at

From one group came Burkette,

first tenor Hugh Geyer and bass vocal Don Miller. The other group consisted of

second tenor Chuck Blasko and another vocalist, Neil

Foster. After rehearsing and getting their vocal harmonies to meld properly,

they named themselves the Val-Aires and impressed a local producer, Elmer

Willett, who later became their manager. Willett produced the Val-Aires' first

release, "Which One Will It Be / Laurie My Love" (Willett 114), and

it sold enough copies in Allegheny County that in Coral Records picked it up

for national distribution (Coral 62177).

"'Which One Will It Be,' was

the worst song you ever would want to hear," said Hugh Geyer, "but it

was something that we enjoyed doing. It's kind of overwhelming when you're

still a high school kid and you've got a recording contract and you're going

into a recording studio and making what you feel at the time was good music. It

was kind of exciting, it really was. Turtle Creek's a very small town, but it

didn't change anything as far as our relationship with our classmates. It

wasn't a big deal. It was exciting for us, but we didn't go flaunting ourselves

as recording artists. We were glad to be singing, we were glad that we had a

record out. It was a song that we wrote, and our producer at the time had

written the other side, 'Laurie My Love.' We thought if we wrote this song,

it's got to be worthwhile. So they pushed that as the A side. Actually, the records

now are collector's items. There's some places in

The Val-Aires then picked up a supporter when the top rock

and roll DJ in

"'Which One Will It Be' was just a regional hit for

us," said Chuck Blasko, "but it's how we

got started with Porky Chedwick and Clark Grace, who

had a powerful dance show at KDKA. After high school, a couple of the guys got

drafted and went into the service, then came out of the service and we got back

together again. We did shows with the Drifters, the Platters, the Dells, groups

like that when they came into town. Porky would bring in those acts. It was

quite a thrill for us."

Before the Val-Aires could have another hit, Hugh Geyer and

Don Miller joined the Army, while the other band members went to college or

found jobs in the factories surrounding Turtle Creek. A few years later, the

five friends decided to record again. "Everybody was bored," said Burkette, "and I said listen, why don't we pitch

together $100 apiece and make some demo tapes."

Burkette, Miller, Blasko and Geyer raised $100 apiece.

Neil Foster, on the other hand, decided to pass the offer up and left the

group. "We messed around in the studio, just doing some demo work, putting

in our own money to record them," said Blasko.

"We were in a studio in

Meanwhile, the Vogues and their manager, Elmer Willette, had found a track they liked, a Petula Clark European hit called "You're The

One." The Vogues released "You're The One" on their own label

(Blue Star 229), and it started to take off. "Nick Cenci

and Co and Ce Records owned a distributing company,

and they started distributing the record," said Blasko.

"Then they came up with Co and Ce Records, and

they took over our contract. We weren't a nationally distributed record

company, but Co and Ce was."

Distributed nationally, "You're The One" (Co and Ce 229) became a breakout hit. As 1965 ended, the Vogues

had their first Top 5 pop hit - and a visit from an old friend. "And as

this was playing as a hit," remembered Burkette,

"Neil called me and he says, 'Hey Bill, I'm going to have a party and I'm

going to have all you guys down, and we'll have some beer and so forth.' I

said, 'Neil, you're not buying in for $100 after we have a hit record.' We

remained good friends, but I told Neil many times, he was just too cheap to

come up with a lousy $100. And in those days, I guess $100 was a lot of money

to come up with, but we took a chance and he didn't."

"'You're The One' was written by Petula

Clark and Tony Hatch," recalled Blasko. "It

was on her album at the time, and that's how we learned the song. Surprisingly

enough, she had a hit with it in

"I met Pet," said Burkette,

"and I thanked her for the hit and gave her a big kiss. She never brought

the hit out to the States, because she knew it was going to be a giant in the

States the way we did it. We lost it in

Even as "You're The One" was rising up the charts,

the Vogues knew another hit was needed - and fast. They knew the story of

harmony groups with one major hit who took too long to get back in the studio

for a follow-up. "Having a hit record was exciting, it was just a great

feeling," said Blasko. "But we still had

our day jobs, working in Westinghouse and the mills here in

Two months after the release of "You're The One,"

Nick Cenci brought them back into the studio for a

follow-up, "

"I was working at Westinghouse Air Brakes, running a

lathe," said Burkette. "And 'You're The

One' was a hit. And all my buddies had their radios near their machinery, and

they're looking at me, and they're saying, 'are you out of your mind, when are

you leaving?' I said, 'When I get the second hit.' I had heard in those days of

so many people having one hit and missing all the rest of them and it didn't

mean anything. I was married at the time, in those days you married young, and

I was not about to give up that security of that little job that I had. So I

said when I get the second hit - and when 'Five O' Clock World' came out - and

it was about a factory, and at

"That's why we continued to work and go out on weekends

to promote the record," said Geyer. "We went as far as we could to

get away from the

And after their third Top 40 hit, a Jay and the

Americans-influenced ballad called "

In July 1966, they performed "

But after "

The Vogues released four more singles on Co and Ce, including a remake of Johnnie Ray's "Please Mr.

Sun," and a peace-and-love song inspired by the motto of the Communist newspaperPravda, "Lovers Of The World Unite"

(which during its release shifted from Co and Ce to

their distributor, MGM).

Other groups might have considered giving up going home,

confident that they made at least an impression in the musical world. For the

Vogues, it meant changing record companies, signing a new deal in 1967 with

Reprise. Reprise gave the group a three-single deal - if none of the singles

charted, they would be released from their contract. The first song, "I've

Got You On My Mind," stiffed on the charts.

Meanwhile, the Vogues took a recording engagement in the

Catskills, oblivious to the fact that their second Reprise single was slowly

climbing the charts.

In 1961, Glen Campbell had a minor chart single with a Jerry

Capehart song called "Turn Around, Look At Me." The Lettermen, who like the Vogues came from

western

"It was an unusual feeling," said Geyer.

"We're up there in the Catskills performing on our previous hits, 'You're

the One' and '

And after performing "Turn Around, Look At Me" on Red Skelton's variety television show,

Skelton presented the Vogues with the ultimate symbol of musical recognition -

their own gold record, commemorating a million-selling single. "You take

four guys out of a small town, and now you're in the major leagues," said Blasko. "The thought of making a mistake or doing

something wrong or whatever, but it all worked out fine. If it would have been

up to Red Skelton, he wanted us actually to come onto his show as regulars

every week, he really liked the group. But we lived in

The Vogues also found that they had found a new musical

niche - mellow, contemporary re-interpretations of classic doo-wop and

four-part harmony classics from the 1950's, songs like "My Special

Angel" and "No, Not Much," performed in new arrangements with

strings and horns and their own vocal wall of sound. "We were able to work

nightclubs after 'Turn Around,' said Burkette. "It got us into the Ed Sullivan Show, the Johnny

Carson show, and it became a standard. And surprisingly enough, 'My Special

Angel,' our follow-up, is more of a standard than 'Turn Around,' being played

more over the country."

"Because of where we grew up, listening to music from

the Four Lads and the Four Aces and the Four Freshmen and the Hi-Los, we just

liked that kind of material," said Blasko.

"We took the full sound that we had with Warner Bros. and added the

orchestration. We used to do 'Over The Rainbow' a capella when we were still in high school. When we went

with Warners, we said let's do this with a big

orchestra, which we did. We thought it was great, we thought it came out really

nice."

By the early 1970's, the Vogues were a trio, as Hugh Geyer

retired from the group to spend more time with his wife and children. "It

was New Years' Eve of 1972," said Geyer, "and I had told the guys six

months before then that I was leaving. I would work with the new guy who would

replace me, I would help audition people. I had just gotten to a point where

traveling and being away from home - I had three young children at the time,

and I said enough's enough and I was going to hang it up. They tried very hard

to convince me to stay, but I had already made my decision. They did not

replace me, they went out as a trio. They may not have

wanted to bring a stranger into the group, but I honestly believe that if they

did, the sound would have been affected unless the guy who replaced me sang

exactly as I did, which was pretty hard to do in a four-part harmony

situation."

Geyer later entered the world of architectural drafting,

working for an engineering firm in

The other members were still recording, but touring was

becoming less and less of an important part of their lives. "When we went

with 20th Century Fox Records, we were down to three guys. Hughie

had left - the high tenor. He was married, he had children. I credit it to the

upbringing we had, family values. The Vogues stopped performing at around 1972.

We were still together, but we didn't tour that much. We returned to the

By 1974, the Vogues entered into a new management contract.

At this point, things get muddy. Even as their third single for 20th

Century, a remake of the 1941 song "As Time Goes By," was in the

pressing plants, both their recording contracts and management contracts were

sold - according to Blasko, without their

understanding - to a third party.

"We were with 20th Century at the time, and

the record company sold the management contract and the record contract to a

fellow that promised the moon - they all do - and in 1974, he trademarked the

Vogues' name. Then he offered to sell it to us!"

Blasko, Miller and Burkette were in a quandry. They were the ones that did all the promotion and

the singing and the hard work, performing up and down the Rust Belt at record

hops and nightclubs and running home to make the Monday shift at the factory.

And now somebody else was going to reap the fruits of their labor?

Copyright law is a double-edged sword in the music industry.

It protects writers and performers from losing their royalties from plagiarists

and copycats and the like. But sometimes that copyright can be purchased or

sold like a Mets catcher. Bands break up, and the former members fight over who

can continue to perform under the old band's name. The record company claims

the band's name in exchange for a fatter royalty payment,

then fires the band and replaces them with anonymous studio musicians. A

popular group records under the name "Starship" because one of their

former members owned the rights to the name "

In the Vogues' case, it meant that even though they weren't

touring any more, a new group of Vogues were. One could almost borrow the

tagline from the Broadway play "Beatlemania!"

- "Not the Vogues ... but an authentic re-creation..."

"The guy who bought our name," said Blasko," was a fellow out of

And Blasko kept an eye on this new Vogues - and he winced every time he heard the lead

singer telling the crowd, "Here's a hit record that we did." And

he grimaced every time the group credited Petula

Clark with writing a song for them in the opening patter to "You're The

One." "It's not only that," said Blasko.

"I can't foresee even somebody saying that they're the Vogues. Because they're not. They may own the trademark - and by

law, they're allowed to say they're the Vogues, but I can't possibly see how

somebody could do that."

The original trio continued to tour, but by 1975, Bill Burkette was ready to leave. He had promised his wife that

if she gave up ten years for his performing career, he would give her the rest

of his years. And the tenth year - 1975 - had arrived. "I put about 10

years solid into the Vogues, from 1966 to 1976, 10 years on the road, away from

my family. I had a couple of kids, and a matter of fact I missed some of them

growing up at that stage in life. I told my wife, give me ten years of your

life, and after the tenth year I'm out of show business. It was New Years' Eve,

in the

By 1975, the original Vogues sued the new Vogues in Federal

Court. In the judge's decision, he gave the original members the right to

perform under the name "The Vogues" - but limited their performing

territory to 14 counties in

Even though he had left the group, Hugh Geyer was sickened

as well by the purchase of the name of the group he performed with for 12 years.

"I'm angry from one standpoint because what they've done is they've

limited Chuck, who is the only member who has a Vogues group also - they have

restricted an original member from 1964 from having the area to perform because

of the legalities of the situation, Terry Brightbill

and his bogus group can appear anywhere they want to, and Chuck Blasko, who is an original from 1964, can only perform in

so many counties in Pennsylvania. But on the other hand, in addition to my

anger, I feel frustrated because I don't understand why somebody would want to

do that. Why would I want to go out and put together a group and say I'm Jimmy

Beaumont of the Skyliners? What personal satisfaction

do I get out of that? Every time I would step on stage, I would be a fraud, because

I would be trying to convince people that's who I am,

all for the sake of money. And that's wrong."

Because of what happened, and to prevent future artists from

getting shafted out of their name, Blasko and other

former musicians and performers have been lobbying Congress for laws protecting

artists from copyright exploitation. "One of my things going into the

hearings is the way they're advertising - I already have newspaper clippings

that say that, a couple from Maryland that says 'The 1960's recording artists,

"The Vogues," will be in concert tonight.' Carl Gardner of the

Coasters has gone through this for years and years. Charlie Thomas from the

Drifters, Herb Reed of the Platters. These guys have spent thousands and

thousands of dollars in court fighting over something that they made. These

trademark promoters and the trademark owners and that, they look at these guys

like you're nothing today - and they were the ones that created it. The

trademark laws are good - but for this situation, something's got to be done.

It's definitely wrong."

Blasko has, however, found a positive outlet for his creative energy. He works

with the newly-built Vocal Group Hall of Fame in

And even if it means limiting his touring schedule to the

Although the Vogues have not performed together since the mid-1970's, they still remain good friends and keep in touch

with each other. The four members got back together in 1999, at Don Miller's

daughter's wedding. As the four friends and performers got together and swapped

stories about family members and life on the road, somebody asked if the four

Vogues would pose for a picture. Expecting maybe one or two snapshots, the

quartet agreed - only to be pleasantly greeted by dozens of camera flashes from

family members who were proud of the group's musical heritage.

And the memories will always be there for the Vogues.

"What I have done recently," said Geyer, "is our den, which is a

small room where we watch TV, I have recently found a place where I can buy

frames which are specifically for vinyl albums, and I have framed all our

albums, and I have the actual vinyl records inside the cover in the frame. And

I started putting those up, and the gold record, and some other certificates

and plaques. I'm just in the process now of going through some photographs that

I have of the Vogues with different celebrities. I have the front cover of aCashbox magazine with the Vogues' pictures on the

front which I'm getting framed. I'm so grateful for the success that we had,

and I tell people all the time this industry requires so much luck. I always

believed that the Vogues were a good bunch of guys, good people who sang well

together. If the other three members would walk in the door right now, we could

start singing immediately and everybody would know their own part and where

they were supposed to be. That's what made the Vogues a success too, was the

tightness that we had as friends - and our families were friends, and we grew

up in a small town and we didn't have big heads, and we tried to keep

everything on an even keel. That's what made the group successful, too."