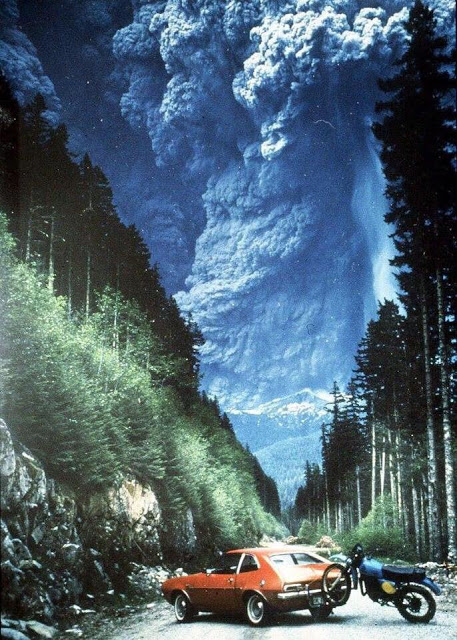

The Story Behind One of the Most Striking Photos of

the Mount St. Helens Eruption After 40 Years

On March 27, 1980, a series of

volcanic explosions and pyroclastic flows began at Mount St. Helens in Skamania

County, Washington, United States. It initiated as a series of phreatic blasts

from the summit then escalated on May 18, 1980, as a major explosive eruption.

The eruption, which had a Volcanic Explosivity Index of 5, was the most

significant to occur in the contiguous 48 U.S. states since the much smaller

1915 eruption of Lassen Peak in California. It has often been declared the most

disastrous volcanic eruption in U.S. history. The eruption was preceded by a

two-month series of earthquakes and steam-venting episodes, caused by an

injection of magma at shallow depth below the volcano that created a large

bulge and a fracture system on the mountain’s north slope.

But for almost 40 years, the context

of the photo appeared lost to time. Where exactly was it taken? Who took it?

And how did they make it out alive? Or did they?

Dan Strohl isn’t sure where he first

saw the photo, but as the online editor at Vermont-based Hemmings Motor News, he’s come across

it a lot. The image is particularly popular in automotive circles—1970s Pintos

famously had rear fuel tanks prone to explode in rear-end collisions, so for

car enthusiasts, the sight of one parked in front of an erupting volcano made

for an apt visual metaphor.

And the more Strohl saw it on

message boards and social media feeds, the more intrigued he became. “It got to

the point where I said, ‘I’ve got to find out what’s going on,’” says Strohl,

who worked in Roseburg, Ore., early in his journalism career.

Last year, Strohl began scouring the

internet for every instance of the photo, in hopes of finding a stray comment

that might hint at who took it. He eventually found one.

A guy on Facebook named Gary Cooper

claimed an old co-worker took the photo. According to Cooper, the photographer

was Richard “Dick” Lasher, who worked with him at the Boeing plant in

Frederickson, Wash.

Richard Lasher spent that Saturday

night packing some gear figuring he’d head out first thing in the morning to

get a look at the mountain before it blew. His plan involved hitching his

Yamaha IT Enduro bike to the back of his Pinto, driving up to Spirit Lake, then

exploring the area via dirt forest roads on the bike. He’d leave before dawn

and arrive at the lake right at daybreak.

Tired from packing, Lasher slept in

an hour or two past his planned departure time. He swore in telling the story

many years later that sleeping in that morning saved his life. Based on the

angle of the photo and the surrounding terrain, it appears Lasher drove down

toward Spirit Lake from the north, likely dropping down from U.S. 12 and the

town of Randle into the forest roads of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. He

possibly made it as far south as Forest Road 26 by 8:32 that morning, the time

the volcano blew.

Had Lasher made it to Spirit Lake,

he’d almost certainly have died. According to John P. Walsh’s description of

the eruption, Spirit Lake “met the full impact of the volcano’s lateral blast.

The sheer force of the blast lifted the lake out of its bed and propelled it

about 85 stories into the air to splash onto adjacent mountain slopes.”

Had Lasher made it even over the

next ridge, he’d almost certainly have died. According to Cooper’s telling of

the story, “Luckily for him, and he did not realize until later just how lucky,

he was on the opposite side of that ridge in front, because the entire forest

was flattened from the ridge down, and he was in the lee side and protected

from most of the blast.”

He did, however, realize that he had

to get out of there in a hurry. Though the volcano blew out a pyroclastic flow

almost due north and Lasher found himself more northeast of the blast, one map

shows that temperatures near where Lasher found himself rose to 680 degrees

Fahrenheit. According to the same map, most of the 57 people who died that day

were positioned to the north or northwest of the volcano, but at least four of

them were in Lasher’s vicinity.

“He pulled over and attempted to

turn around seeing as the ash cloud was heading his way and fast. In his hurry

he bent the forks on his motorcycle,” Cooper continued. “He jumped out of the

car and ran up the hillside to get some pics, thinking he might just die for

it, and hoping someone would find the camera at least as it was a phenomomenal

sight that filled the sky. The first picture he took was the one with the Pinto

cocked in the road and the bent motorcycle still in the back with that HUGE

cloud going up in the sky in the background.”

“He made his way back down the

mountain after being quickly overtaken by the ash cloud. He was completely

blinded, and had to drive on the opposite side of the road steering by staying

right on the opposite side of the road heading into oncoming traffic, but

encountered nobody going up. The car choked out after a while and he rode his

bent motorcycle out of the mountains back to the room he had rented.

“The next day as soon as he could,

he rode his motorcycle back up into the now really hot zone with his camera to

get what pics he could. He was well into the red no go zone, when a helicopter

saw him, and came right down and landed in his path. He was surprised to be

arrested on the spot and flown out in the chopper and to jail. They left his

motorcycle lay on the mountain. They also kept him in jail for a few days

without letting him call anyone or even plead his case. When he finally got

out, he again went back up there, (Not sure how) and was able to get his

motorcycle back and I think later his car as well.”

Some of those photos that Lasher

ended up taking of the aftermath, according to Cooper and fellow former

co-worker Steven Firth, focused on those who didn’t make it out alive and on

the automotive wreckage they left behind. Both Cooper and Firth recalled Lasher

showing them photos of burned-out vehicles with puddles of melted plastic

underneath.

So, yes, the photographer behind

that mystery photograph did survive to see it widely disseminated. Whatever

became of the Pinto and the Yamaha, however, we don’t know. “So if you have a

red Pinto hatchback with a lot of volcanic ash in the seams,” Strohl wrote in

his article, “get in touch with us.”